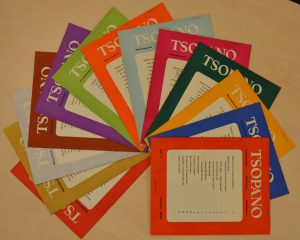

This week we have sent away the first batch of archive material to be digitised! In this batch we’re digitising some photograph albums that include pictures of political events, from Kamuzu Banda’s homecoming to the first general election in 1964, Mackay’s own idyllic travels around Central Africa and images he hoped to include in a proposed book Portrait of Malawi. In addition to these photographs, we’re sending away some of the key periodicals that Mackay had a hand in – of these, we have already discussed a little about Tsopano, but here’s some more about the magazines joining it: Concord and Malawi News.

Concord’s artist Jean Maynard adapted a painting by Toladi from the Art School, Brazzaville, French Equatorial Africa, for the cover of this Royal Edition.

Concord was the magazine of the Interracial Association of Southern Rhodesia which was founded by Hardwicke Holderness – an MP in Garfield Todd’s Government who supported full equality between races – in 1953. Mackay was with the publication from the very beginning and helped move it from an idea to reality.

The aim was for Concord to be the first multiracial publication in the colony and this is reflected in its content which ranged from impressions of Parliament written by MPs of the day to articles on the various celebrations of different ethnicities and religions such as Ramadan and Deepvali and a series of articles on indigenous Rhodesian art and Bantu culture. Though politics featured regularly in the magazine, its topics were eclectic – encompassing literature (a short story by Doris Lessing), history (excerpts from – of course! – Dr. Livingstone’s account of Victoria Falls) and popular interest pieces.

Our run of Concord spans the years 1954-1958 and includes the ‘Royal Number’ which celebrated the visit of the Queen Mother to Southern Rhodesia in 1957.

While Mackay describes the Interracial Society as having faded out of existence and having been ultimately unable to inspire the ‘communal sense of sharing’ it had set out to instil, he kept this run for posterity – perhaps for pragmatic reasons with regards his profession but perhaps also as a reminder of his first distinct move to help bridge the colour bar. Though Mackay himself admits that this move was more an ‘accidental stumble towards tomorrow’ than anything, his involvement in these societies lay the foundations for what was to come.

Throughout much of his archive, Mackay expresses a keen awareness of the difficulties of including white Europeans in the cause of African Nationalism. He describes the tendency to think of white liberals as ‘wishy-washy’ in his book We Have Tomorrow, citing what he considered to be the weak attempts of the Interracial Society and the Capricorn Africa Society as reasonable demonstrations that this was, largely, an accurate surmise. After his incidental start along this path, Mackay attributes the conversion of his ‘own wishy-washyness’ to ‘something more combative’ and his striding more confidently and purposefully towards that tomorrow to Operation Sunrise.

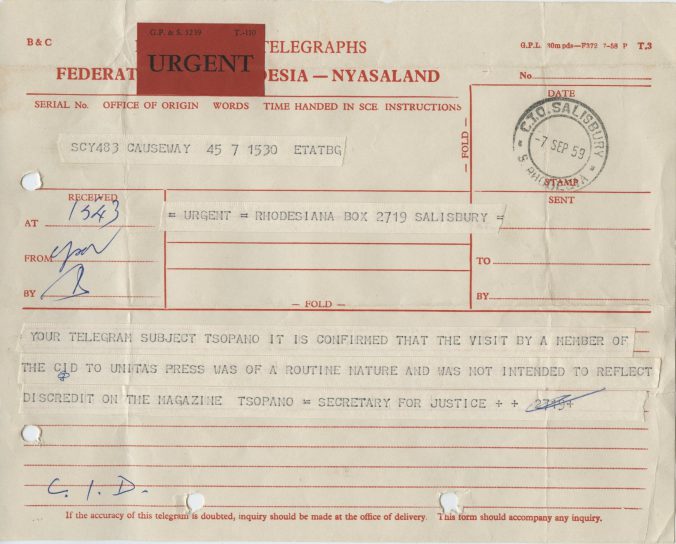

Operation Sunrise was the name given to police action taken on the 3rd March 1959 when governor of the Central African Federation Sir Robert Armitage declared a state of emergency “because of the action of the leaders of the Nyasaland African Congress”. The aim was to arrest 350 people that the government felt were threats to law and order following a renewed move towards independence made by the NAC after appointing Kamuzu Banda as their leader. Those arrested were imprisoned without trial and waited months in jail for Macmillan’s government in the UK to order their release.

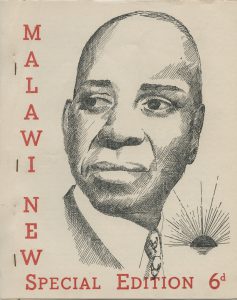

The final periodical we are digitising in this round exemplifies that movement towards action that Mackay felt after Operation Sunrise. With the key members of the NAC imprisoned and the organisation banned, Orton Chirwa established the Malawi Congress Party and held its position as President in safe-keeping until Banda’s release. Aleke Banda took up the interim role of Secretary-General and edited Malawi News – the official party newspaper from its inception until he left for scholarship at Harvard in 1962 when Mackay took over the role as editor until a suitable African alternative could be found.

We have a run of the initially fortnightly and eventually weekly run of Malawi News from January 1960-January 1961 which includes Special Editions – notably, the edition given over to the release of Kamuzu Banda from Gwelo – and bilingual articles.

Edition celebrating Dr. Banda’s release from Gwelo prison, 2nd April 1960

The magazine is a fascinating source of information on the political climate from a very singular point of view, offering an interesting look at a reporting style that was at times unpolished and often displayed open bias. The insight it offers into the propaganda surrounding and sustained by the MCP and its leader, Dr. Banda is remarkable – to the extent that Mackay, in notes he makes on the editorship of the publication (presumably in his brief period filling in, certainly they appear among papers of that period), writes that “lots of things happen which are not recorded in MN and, I am afraid, sometimes this is due to ‘forgetting’ to write about them rather than ‘not knowing’ they had taken place.”

Despite a harsh critique of the administration of the newspaper in these notes, commenting on everything from the overall appearance of the finished product to the literary efforts of the journalists, Malawi News obviously held a place in Mackay’s heart – perhaps even just for being a tangible example of the rise in open popularity of a movement he championed so strongly.

“Will you ask Kathewera to send me a copy of Malawi News Vol II No 52. I will then have a complete set of the first year’s issues to give me joy when I look back on them in my old age”

– Peter Mackay to Aleke Banda, 18th February 1962

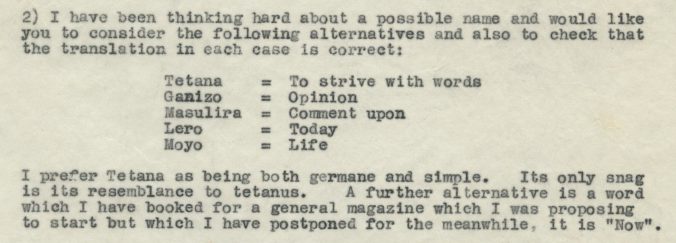

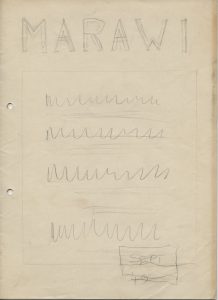

So the three periodicals we have sent away for digitisation mark three very distinct and important stages in Mackay’s interaction in the politics of Malawi. Concord shows us his beginnings, his original understanding that the colour bar was not something he agreed with. Tsopano illustrates Mackay’s efforts to let the African voice be heard in the struggle for independence and Malawi News reports on the events that would see the struggles of Mackay and so many others bear fruit.

We can’t wait to be able to share the digitised versions!

Malawi News: Thandika Mkandawire, Musosa Kazembe, Matthews Ndovi, Mackay and Aleke Banda, c.1962