Whenever Peter Mackay refers to his ‘career’ in his personal papers, he is referring to his work as a journalist. Whatever else he may have accomplished in Africa we might have to describe as his extra curriculars or his passions, maybe more of a lifestyle choice than anything.

From corresponding on Rhodesian Farmer in the late 40’s and early 50’s, Mackay went on to contribute to many local, national and international journals and newspapers and he had an editorial hand in a number of the same. Having said that, I consider Tsopano to be Mackay’s first brainchild. Perhaps it’s because he kept production files for each issue which are crammed with articles edited both for reasons of space and reasons of prudent censorship, interviews, correspondence and administration for the day to day running of a magazine. These files are also contained in the archive and they illuminate the workings of editorship so brilliantly that I began to feel like Tsopano was the crowning glory of all Mackay’s journalistic endeavours. This may or may not be true, but he certainly took great pains to preserve everything to do with the production of the magazine – and created his own notes on the material 35 years after the fact.

“My own interest in a publishing venture in Nyasaland actually began last year when it seemed clear that something was needed to counteract the one-sidedness of press coverage in and about Nyasaland… But whereas before – and always – my thoughts were directed towards trying to condition the attitudes of people of my own race, I now began to think in terms of something which would genuinely help to articulate the little-known and certainly misunderstood cause of African nationalism.”

Personal correspondence, November 1959

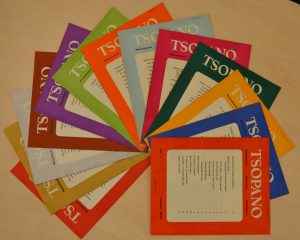

So what was Tsopano? Tsopano was an anti-Federation magazine published from 1959-1961 by Mackay originally in Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia for Nyasas in Nyasaland. It ran for 13 issues (all of which are contained in the archive). It was published entirely in English, though Mackay expressed the hope that it might eventually appear in Chinyanja too, because to further the cause of the magazine – which was to present as unbiased an account of African feeling within Nyasaland as possible – Mackay wanted influential English-speakers to be able to easily access the information therein. Indeed, he counted Harold Macmillan as one of his readers among many other high ranking and influential English speakers.

Tsopano sought to inform Nyasas on key government initiatives such as the Devlin Report (1959) and the Monckton Commission (1960), enable constructive criticism of the current political regime and discuss hopes for the future of Nyasaland – no mean feat when the colonial Government had declared a State of Emergency in March 1959, imposing Emergency Regulations which effectively acted as several modes of censorship.

Whilst the magazine was sympathetic to the views of the Malawi Congress Party – how could it not be when they were at the heart of the anti-Federation movement? – and wrote on its members and their activities often, it’s overriding aim was to “provide a true and genuine medium for the expression of African opinion in Nyasaland”. As such, letters to the editor that expressed anger and opposition to the main tone of the periodical were also published from time to time (though it has to be said that the vast majority of correspondence kept in the production files are letters of admiration for the work Tsopano was doing and whole-hearted support for Kamuzu Banda, the leader of the MCP). And Mackay seems to have been sensible of the accusations that might be made of such a magazine, writing in a letter early on in the planning process that Tsopano “does not have among its objects the role of being his [Banda’s] mouthpiece (though its contents will undoubtedly be sympathetic to his views insofar as these are closely identified with ‘expression of African opinion’)…”

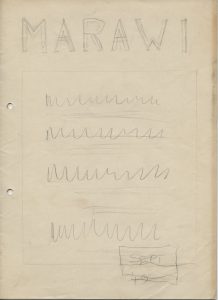

This must be a very early doodle of what the magazine was to look like as ‘Marawi’ was discounted as a possible name early on in proceedings.

Careful consideration went into the naming of Tsopano. Mackay tells us in We Have Tomorrow that they had originally thought to use the Chichewa word ‘marawi’ but Kamuzu Banda had asserted that he had different plans for such a name. ‘Marawi’ which literally translates as ‘flames’ became adopted by the Malawi Congress Party – the political party that arose from the ashes of the banned Nyasaland African Congress party in the aftermath of Operation Sunrise (1959) and the symbolism of the phoenix rising from the ashes was deliberately evoked in terms of the party and of the country itself.

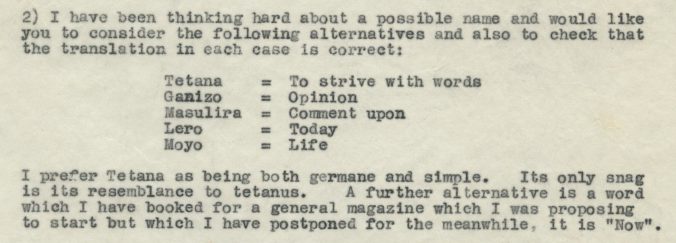

So Mackay and his friends were back to the drawing board for names for their periodical. In a letter to his friend and frequent contributor to Tsopano, Jimmy Skinner, Mackay suggested a few Chichewa words chosen for their directness of meaning. ‘Tsopano’, the Chichewa for ‘now’ seems like an afterthought in this discussion but something about it must have appealed to Jimmy because there are no extant mock-ups of any names other than Marawi and Tsopano.

Cover mock-up for Tsopano issue 1

Mackay explains in his book We Have Tomorrow that Tsopano’s overall presentation was intended “to match its serious purpose without being ponderous” and it’s true that there isn’t much that’s visually enticing within the publication. The only photos ever produced are of the Malawi Congress Party conference in Nkhota Kota, 1959 which are Mackay’s own and are also contained in the archive. Illustrations are also few and far between, reserved for key members of the MCP. However, Peter Mackay’s production files are rife with more artistic contributions to the magazine that never make it to print: poems, songs, moralistic tales (my favourite of which is entitled ‘Story of a Wild Pig’) are all sent in by readers keen to voice their frustrations and their hopes but in a more artistic manner. In one response to such a contribution, recorded in the production files, Mackay explains that while space is so limited the editors of Tsopano do not feel they can justify granting inches to items that do not deal directly with political issues.

Despite the above, I enjoy noticing that Mackay couldn’t help himself. The subject matter and its representation might be weighty and thought-provoking but the look of Tsopano as a magazine is bright and cheerful – maybe intended to represent the catharsis and optimism Mackay hoped the magazine and its subject matter would inspire. I like to think of him choosing what lurid colour the next cover would be – an imagining helped along by a comment he made in a letter describing his search for a green that was ‘suitably bilious’ for issue 4. Not only this but in the last issue of Tsopano printed as 1961 dawned in Nyasaland, the year when the Malawi Congress Party would finally win the election and set the wheels of change in motion, Mackay finally printed a poem that had been sent in to Tsopano HQ entitled ‘Thought for the New Year’.

The full run: from the bilious green issue 4 to the silver and gold issues 11 and 12

Tsopano tried to toe the line that Nyasaland’s Emergency Regulations instilled, struggling always to avoid condemnation from the government, regretting the lack of wholly open free speech that they could afford their contributors but always allowing that Tsopano, a much needed vent for the people of Nyasaland, with limitations was ‘better than no Tsopano at all’. Because of this, the study of this periodical and its corresponding production files is also an interesting foray into a world of censorship and defiance of that censorship. From the very first issue Mackay strives to advise on how best to do this – issuing a statement laying out the restrictions that Tsopano faces in no uncertain terms and suggesting constructive criticism rather than open hostility as being the best way of expressing ones views without contravening the rules in place. Even so, some of the editing of letters and articles in the production files makes for incredibly interesting viewing: in and amongst the grammatical corrections and standard truncating of long text are the sentences and paragraphs mostly likely crossed out because they were too bold or passionate to be printed.

“I am still not at all happy at the way the contents suffer from the legal paring they have to undergo.”

Personal correspondence, November 1959

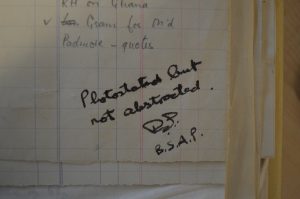

The road to publishing such a series as Tsopano was not smooth. CID intrusion at the initial stages of printing issue 1 forced the original printers to decline to work with Tsopano and ensured that the ensuing printers were kept in the government’s pocket and allowed regular inspection of the copy. Indeed, Mackay’s first production file notes that some of his papers had been taken away without his knowledge, examined by members of the British South Africa Police and returned with their signature – a forceful reminder of why the magazine strove to keep its criticism constructive.

‘Stamp’ of the British South Africa Police which Mackay could not account for when drawing up notes for his production files 35 years on

Though there had always been plans to give control of Tsopano over to Malawis once the MCP were in a better position to oversee its publication and, indeed, Mackay sometimes referred to Tsopano as having been subsumed by Malawi News in correspondence to his friends and acquaintances in the 60’s, Tsopano ceased suddenly some way through preparations for issue 14, perhaps due to a lack of funds foreshadowed in Issue 13 in a statement made about Government pressure restricting revenue from advertising.

But though Mackay may have felt that the nature of Tsopano demanded that he only held control of it temporarily while those who ought to have control were imprisoned or otherwise oppressed, his thirst for action and love for his profession dictated that he start up another magazine – Chapupu II – just over a year after Tsopano ceased business.

Mock-up for the unpublished issue 14