“The Defence Act amendment providing for the compulsory registration of the 18-50 age group applies only to Northern and Southern Rhodesia. Nyasaland residents are excluded… Needless to say I haven’t registered myself – this being a straightforward decision of principle – but the dilemma I’ve been pondering is the one you mention – to flaunt one’s refusal or quietly await the consequences. There is a lot to be said for both alternatives, but my inclination is to make an open gesture of defiance. I suppose really that one is duty bound to do so (fruitless though such a gesture would be) but I have not finally made up my mind.”

– personal correspondence, 25th March 1962

Section 28 of the Defence Act, No. 23, of 1955 as amended, as read with Federal Government Notice No. 278 of 1962 stipulated that all British or British protected males in between the ages of 17 and 50 (inclusive) who had lived in Northern and Southern Rhodesia for six months or longer had to register themselves for what was termed ‘peace training’. The Defence Act was a controversial piece of legislation – indeed, Mackay understood and noted in his personal correspondence that Sir Robert Tredgold resigned as Chief Justice in the early 1960’s in protest against it. Mackay himself was certainly not amenable to its contents, describing peace training as a ‘racially-contrived territorial force’.

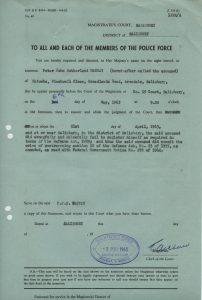

Arrest warrant, 1st May 1963

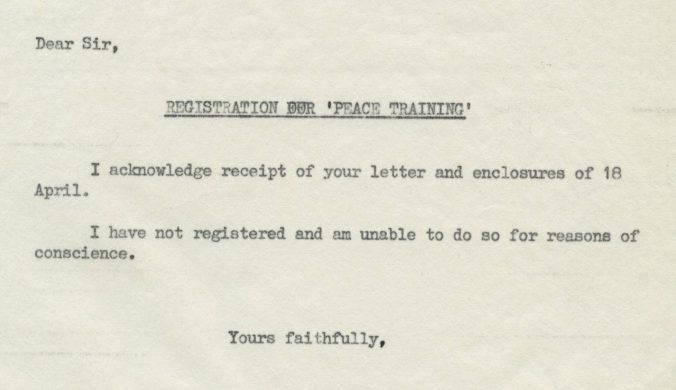

As such, Mackay did not register for the training and when he was sent registration forms reminding him that his obligation was unfulfilled, he replied that he was unable to register for reasons of conscience.

I haven’t yet come across any evidence to suggest that Mackay did make the open show of defiance that was discussed in correspondence with his friends but nevertheless, his defiance was noted and the first warrant for his arrest we have in the archive was circulated on 1st May 1963. As a result he was fined £60 and given a suspended sentence of two months hard labour. But the offence was a continuous one, meaning that new papers for registration were sent out to Mackay and a second refusal to sign up would result in a second prosecution where the consequences would be more severe and the suspended sentence from his first offence would be activated.

“I have been trying very hard to find a reasonably honourable way out, but can’t.”

– personal correspondence, 9th May 1963 on discovering he had been sent new registration papers

In the end, the only honourable thing Mackay could see to do was to stick to the course his conscience had dictated to him and he sent another polite refusal to register which precipitated a second arrest and court hearing and a sentence of four months in prison.

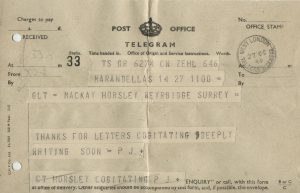

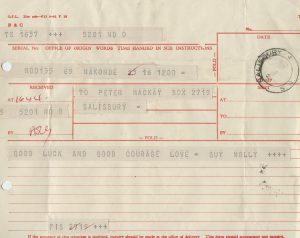

Telegram wishing Mackay luck in court, 16th July 1963

As an automatic remission of 10 days for every month served was applied to those inmates who behaved well enough and didn’t have any of their kit stolen, Mackay was released on the 6th October 1963. During his time in prison, Mackay received much correspondence from friends, even if he could not write back to them and upon his release, he found catharsis in responding to one such friend with a lengthy description of what it had been like in prison, giving a colourful insight into then men who were there with him and the colour bar that was active even within the prison system.

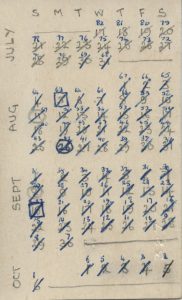

“Even so soon after coming out it is difficult to realise how preoccupied one was with the passing of time. Serving time is a more appropriate phrase than it appears. Certainly time never serves prisoners. I used to cross the days off and work out absurd calculations about the proportion still to go” – personal correspondence 29th October 1963

Calendar kept to mark the passage of time in Salisbury prison

Mackay claimed to have no regrets on serving his sentence, feeling that if nothing else, he now at least knew what to expect should he have to serve time again. A possibility which might have felt more probable than he would have liked when he received another set of registration papers shortly after his release. While the trail in his personal papers becomes muddled at this point, it is clear that Mackay continues to undergo appeals concerning the case well into 1964 with further prosecutions in 1965 – a lengthy and, as he predicted when he first received the phone call confirming the intent to prosecute, expensive process.

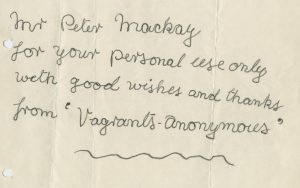

Throughout my perusal of Mackay’s personal papers, I have always been struck by the amount of correspondence he received asking for loans of money or the purchase of important items for acquaintances. They are often names that don’t crop up often in correspondence with Mackay but are still, nevertheless, people who knew that he was a man who would give all the help he could. And it is because of this that it’s so heartwarming to see that in Mackay’s own hour of need, help was at hand without his even asking for it. Aside from financial support from a close friend, Mackay’s lawyers also received anonymous donations of money from the ‘Mackay Defence Fund’ towards the cost of their services. Such must have been Mackay’s reputation for philanthropy that a note kept in his papers specified that another anonymous donation be used only for Mackay’s own personal use.

Mackay had ‘retreated’ to Malawi following his stint in prison in 1963, returning to Southern Rhodesia in 1965 in an attempt to resume his career there. When a warrant for his arrest was once more circulated, Mackay left and finally renounced his Rhodesian citizenship later that same year after Rhodesia’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence which was considered illegal by Britain, the Commonwealth, the United Nations and – more importantly for a man so driven by his own notions of what was and wasn’t conscionable and honourable – Mackay himself.