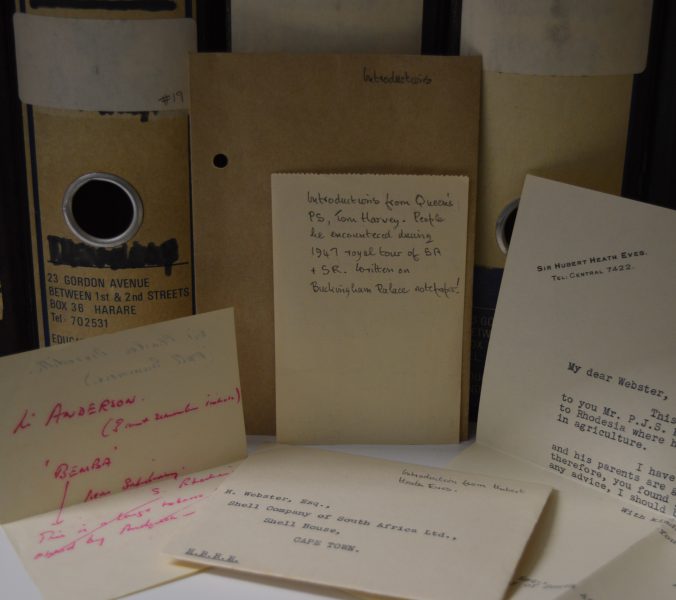

Letters of introduction kept by Mackay and a note of people to whom introductions were sent by the Queen’s personal secretary – on Buckingham Palace notepaper!

I had intended a different first post for this blog, one that started at the beginning of my cataloguing and would proceed as I did – that was until I stumbled across the letters of introduction written by friends of Peter Mackay on the occasion of his emigrating to Southern Rhodesia in 1948. Then I suddenly thought that perhaps I should introduce him too.

Whilst his youth speaks to a certain determination and propensity for hard work that Mackay would later devote to his political interests – he was head boy at Stowe School and the youngest soldier to be made Captain in the Brigade of Scots Guards – and his adult life was one of activism and philanthropism, I wanted to start with something less deterministic and perhaps more personal.

Over the coming weeks, the material in the collection will highlight the very rich involvement in the liberation movements of southern Africa of a remarkable man. But first, I’m going to focus on a couple of gems I’ve unearthed that tell of the everyday Peter Mackay who kept two beautiful bull mastiffs, whose hero was Dr. Livingstone and who, no matter the political crisis, always managed to write home to his mother. The joy of this archive is that you get to learn about it all.

The earliest surviving information on Mackay’s emigration we have are some meticulous accounts of his journey – vivid and leisurely accounts that he wrote to his mother and practical information that was passed around the passengers on the plane concerning their flight.

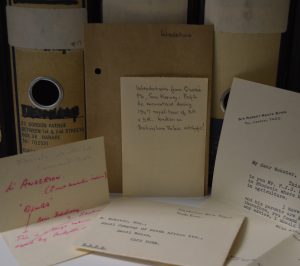

Telegram home 1949 – ‘Cogitating deeply, writing soon’. I must remember to use that excuse…

From this moment on, Mackay wrote regularly to his family but none more so than his mother, whose replies are also contained within the personal papers files in the archive. His extensive correspondence provides a unique insight into his responses to the world in which he found himself and the reactions he had to it that would define his actions.

When Mackay moved to Southern Rhodesia in 1948, it was with an idea to take up tobacco farming. How he fell into journalism instead isn’t entirely clear, though the links between his intended profession and Rhodesian Farmer, the first journal he worked for, are apparent. The most obvious nod we have in Mackay’s own papers of this other life he might have lived are two newspaper cuttings that he kept detailing the drought that affected tobacco and maize farmers in 1951. A part of me wonders why he kept these newscuttings – was it his evidence that toboacco farming would never have worked out for him anyway?

Articles from The Bulawayo Chronicle and The Sunday Mail, March 1951

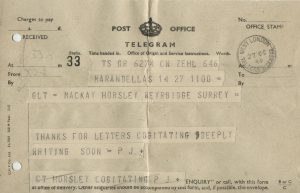

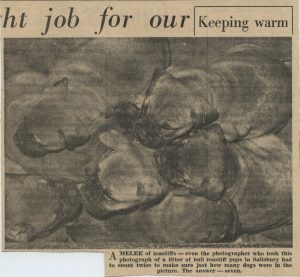

As I made a start on this archive, I was often in awe of Peter Mackay because of his intense involvement in the causes he believed in and so when I found some common ground between us in his archive, it leapt out at me: Peter Mackay was a dog man. In 1954, Mackay’s bull mastiffs Salima and Sir Accolon Pendragon (Sally and Nacky to their friends) had puppies and he kept all of the resultant media coverage one would hope that seven adorable puppies might inspire.

A Melee of Mastiffs – The Rhodesia Herald, June 29th 1959

In addition to this – and this is my favourite thing that I’ve found in Mackay’s personal papers – when Mackay returned to the UK for Christmas later in 1954, leaving Nacky and Sally with some friends, such was the bond between a man and his dog that Nacky wrote Mackay letters informing him of the antics of the humans and the latest developments with his many ladyfriends.

“Met a friend and discussed high politics – we sounded very learned and looked it as well – I wonder what he was talking about?”

Sir Accolon Pendragon

‘late of other places and now of Marlborough in Southern Rhodesia’

I always find it interesting to know the kinds of things that inspire remarkable people and so now to Peter Mackay’s own hero, Dr. Livingstone. Livingstone crops up in the Mackay archive from time to time in many forms – a postcard to Mackay’s mother of Victoria Falls or a letter to National Geographic suggesting that they tie in their coverage of Queen Elizabeth’s inaugurating of the Kariba hydro-electric project to the upcoming centenary of Livingstone’s expedition around the area. But no-where more so than in his own writing where he quotes passages from Expedition to the Zambezi and recounts stories that have already provided me, and I suspect will continue to do so as I delve deeper into the archive, with a beautiful context for items that I thought were simply incidental.

“The biggest, the flagship… was the m.v. Ilala II. The first Ilala had been built on the Thames at Tilbury and commissioned in 1875. It had been named after the place where Livingstone died and brought to the Lake of Stars [Lake Nyasa] in a journey epic even for a century of epic journeys.”

We Have Tomorrow

From the Voyage of the Ilala series, 1958

When my preliminary dig through Mackay’s own photographs produced this marvellous series of images entitled ‘Voyage of the Ilala’, I thought nothing further of them then that they were picturesque images from Mackay’s travels. But not only does the above extract show us the link between this boat and Mackay’s hero, suggesting that there was nothing incidental about Mackay being present to take these photos, but his own account of the story of the first Ilala goes to show just how much the ship’s voyage may have mirrored – or even inspired – Mackay’s own desire to provide aid:

“…the Ilala encountered a dhow plying to the eastern shore. On board were captives bound for the slave markets… on the poop [Lieutenant Young of the Ilala] had a two-pound gun, aggressive use of which was forbidden by the mission’s orders. One shot was sent across the bow of the dhow in the traditional and unmistakeable seafarer’s message. The sail came down, the slaver hove to, the captives were freed.”

We Have Tomorrow

Sunset from the Ilala, 1958

Finally, and just as a point of interest, all of Peter Mackay’s photographs, papers and correspondence are so meticulously filed and labelled that, dare I say it, he wouldn’t have made a bad archivist in another life, either.